As yesterday was Mother’s Day it seems like an appropriate time to reflect on one of the things that’s changed most for me since giving a birth: my body and my evolving relationship with it.

It took me about eighteen months postpartum to buy a new pair of jeans. Over the past decade I had amassed a nice collection of vintage denim, with the crowning gem being a pair of 1980’s Wranglers that fit just right. Not too cropped, not too high in the waist, perfectly straight. I was certain they would be back in my rotation before my son turned two. But two came and went, and the Wranglers still stare at me from atop a pile of untouched indigo.

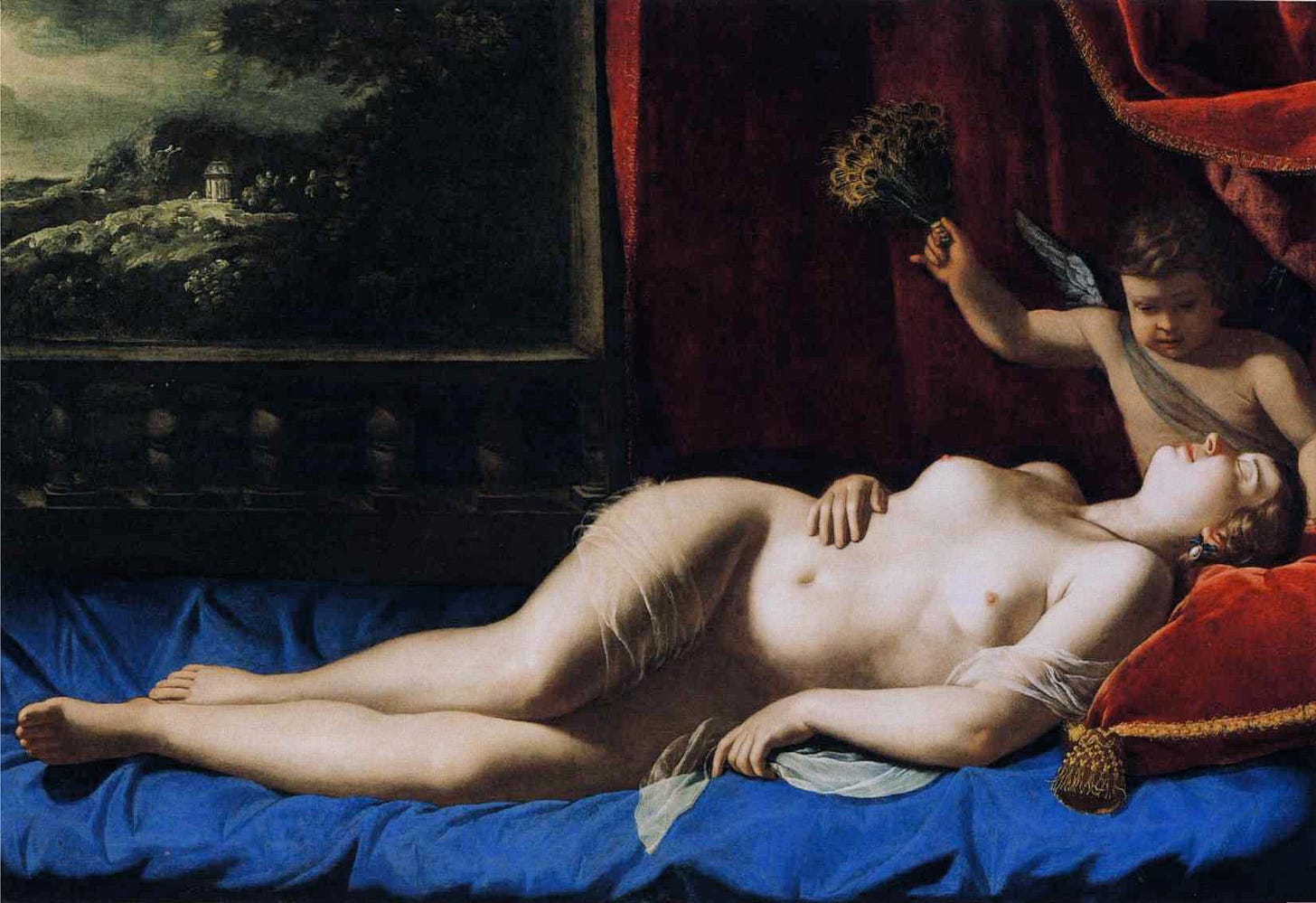

It’s easy to exalt the pregnant body. It’s obvious and sacred and exciting. A couple of weeks away from my due date, a woman at the grocery store caught sight of me in a flowing blue dress and literally did a double take, stepping back and exclaiming, “Whoa! That is a special baby.” I think my at this point enormous belly, shrouded in royal blue did give a rather astounding, Virginal impression. But I wonder now if she’d be so generous with my ever-soft and untoned postpartum figure.

Throughout my adult life I’ve always hovered around a size 4, but I can only identify about a three year period of my life where I felt satisfied with my body. In the pre-social media mono-culture that I grew up in, every model, actress and pop star had limbs with seemingly no fat (save for Jennifer Lopez, whose butt I think actually saved my sanity). I still feel nauseated when I see contemporary fashion that emulates that particular emaciated look. Luckily, by the time I reached my 30’s the images of feminine bodies that saturated popular culture had evolved into a broader spectrum of sizes and colors, and I also had grown more comfortable with the shape of my bones. I rock climbed with near obsession; I felt strong and energetic, even if I never had a thigh gap.

Still, it took me a while to come to terms with the reality that my post-pregnancy body was not, in fact, “bouncing back.” As a tween and teen I constantly contended with images in the grocery store check-out line asking, “is it a baby bump?” whenever a female celebrity exhibited the slightest mound in her stomach, or had she dared to eat a sandwich? Logically, I knew this dissection of physical appearances was vile, but I subconsciously found it impossible not to internalize.

A major propagator of the “baby bump” and “bounce back” narrative was Janice Min, former editor of Us Weekly and The Hollywood Reporter. In an ironic turn, after becoming a mother herself, Min reflected on her role in perpetuating the specter of the pre- and post-childbirth mommy-body. Min writes about getting a manicure four months postpartum and the nail technician peppering her with questions, including about when she was due. “Sometimes, in my sleep-deprived nights, I ponder our ideal of this near-emaciated, sexy and well-dressed Frankenmom we’ve created and wonder how to undo her.”

I felt a degree of relief when, a year after giving birth to twins, Beyoncé spoke about her changing relationship with her body. “I have a little mommy pouch,” she said, “and I’m in no rush to get rid of it.” (Reader, she did in fact get rid of it.) This was the first time I registered anyone, famous or not, proclaiming that a postpartum body was something of which one could be proud. In her first photo with her twins, between drapes of fuchsia chiffon and a cascade of roses, that little mommy pouch indeed peaks out (albeit airbrushed and cast in shadow).

While writing this, an image unexpectedly came across my Instagram feed that more closely resonated with my experience of the postpartum body than Beyoncé really could. Here is Munchie, as she is known, one of the enigmatic geniuses behind 2girls1bottl3, the best social media performance art of which I’m aware. She doesn’t look regal. She doesn’t look overjoyed or proud or blissful. She doesn’t look like she’s about to compete in Mrs. World. In an act of true Internet subversion, she has shed her blue-eyed, bewigged, hyper-presentational persona and just looks like a tired, sweating human.

One day on the beach this summer I noticed that every woman of a certain age was dressed in some version of a burqa. A burqa for the torso, in shades of dark blue and black. No rolls of belly flab, no crinkling stretch marks, no dimples or dark spots to be seen. Possibly some décolletage and bare shoulders, but more likely a veil of linen or chambray to prevent further skin damage.

I mentioned it to my partner—“do you see how all the grandmas are hiding their bodies?”—and he, of course, was not phased by it. What else would they do? Walk around in thongs and pushups like the teenagers do?

“That’s probably what they’re comfortable in,” he said, completely logically. But the absolute uniformity of it irked me. Why does that make them comfortable?

Martha Stewart’s cover of Sports Illustrated was lauded for depicting the aesthetic ideal of “aging gracefully,” thanks to a nice chunk of her $400M fortune being spent on world-class facials, tasteful plastic surgery and the best veneers that money can buy. But the only thing this type of imagery does is further ingrain the existing paradigm of beauty standards, the supremacy of youth, and the acquisition of such.

, who I will never stop referencing, wrote:Stewart is being celebrated for remaining conventionally attractive well into her old age thanks to significant cosmetic intervention and investment. We need to stop pretending this kind of thing is revolutionary. I’d be very into this cover if the headline read something like, “Octogenarian Illustrates How Submission To Beauty Standards Is Always Sexually Appealing To Those Who Have Been Conditioned To Find Women Who Comply With The Patriarchy’s Aesthetic Demands Attractive (Even If They Don’t Realize That’s Influencing Who They Find Attractive & Why)!”

DeFino further laments that “graceful aging” is really just anti-aging, which fundamentally is agist. Being pro-wrinkles exists on the same spectrum as being anti-wrinkles; when will the existence or non-existence of our wrinkles be irrelevant? With social media, you don’t even have to be old to be ensnared by agism. TikTok is full of anti-aging products marketed toward young people and even children (“preventative!” they insist).

It’s not that I think everyone needs to go around flaunting their every ripple and crevice. What troubles me is the lack of nuance or space for expression for anyone who diverges from our culture’s beauty standards. I want the grandmas on the beach to wear whatever they want—or to all wear the same outfit because it expresses their truest vision of their identity, and not because it prevents them from being gawked at, or worse. It deflates my spirit that the surest way for a woman over the age of 35 to feel comfortable in the world is to have her body more or less concealed.

The scrutiny of the shape of female bodies has existed as long as female celebrities and visual media has existed, and probably long before then. During the English Restoration comedy period (1660-1700), actresses performed on stage for the first time and their presence was both liberating and humiliating. Female characters were frequently portrayed as little more than giant, consuming orifices, and many of these plays featured breeches roles in which women were permitted to dress as men or boys, thereby empowering them to behave on the stage as men would and also revealing their figures to audiences, making them subject of bawdy scrutiny. The privilege of performance was met with the double-edged sword of objectification.

Today, not only does social media foist impossible physical ideals and judgment upon celebrities, but now we are all cast as public figures, subjected to and constantly ingesting the critical “male gaze.” We’re constantly scrutinizing and comparing ourselves and the people we see on our screens, venerating an ideal of beauty that benefits pretty much no one. It’s old news that social media is particularly detrimental to the mental health of young women and children. TikTok filters and generative AI further extend this dehumanization and mortification, terrorizing us into looking younger, thinner, more tanned and clear-skinned.

So how did I learn to stop worrying and love my body?

A couple of years ago I discovered the podcast Maintenance Phase. Aubrey Gordon (author of What We Don't Talk About When We Talk About Fat and subject of the documentary feature Your Fat Friend) and Michael Hobbes (host of the podcasts If Books Could Kill and, previously, You’re Wrong About) debunk “the junk science behind health fads, wellness scams and nonsensical nutrition advice.” One experiences a certain degree of schadenfreude listening to the hosts recount the demise of various “wellness” charlatans, but the backbone of the show is science and statistics. I found it affirming to confront the myth that “hard work pays off,” and even worse, “dieting works,” when in reality, so much of what we contend with in pursuit of “beauty” is determined by genetics and entropy.

Through the noise of social media I also found wonderful independent creators like sass.and.cellulite and myemtv who confront insecurity and fat-phobia head-on, with humor and panache (I’m sure you can imagine the vitriol they receive for daring to reject diet-culture). They look at ways in which corners of the fashion industry boast of inclusivity, but more often than not it is a hollow gesture because the “inclusive” sizing isn’t adjusted to properly fit bigger bodies; brands just size up their garments that are intended for smaller bodies, making the fit absurd and clownish for bigger bodies. Some of their content also reminds me of language I heard growing up about certain foods being “bad” or “guilty pleasures,” when in reality food is food and there is nothing moral about it. (Update: A previous version of this article referenced Remi Bader and her critique of fat-phobia; Bader has since walked back a lot of her advocacy so I’ve chosen to remove her as a point of reference.)

I am not trying to conflate my body dysmorphia with the very real prejudice faced by fat people, and pretty much anyone non-Western conforming. But the confidence, determination and emotional vulnerability that these women demonstrate has helped me realize how well my body serves me as it is, even if these days I feel soft and tired more often than I feel strong and cute.

The “body positivity” movement originates in the fat activism of the 1960’s, which sought to dignify persons of all sizes, ability and status by securing them equal access to all spaces. Today it has been widely co-opted and diluted by the beauty and wellness industry seeking to sell us an endless supply of serums, tonics and elastic pants. More interesting to me, at this point, is the concept of body neutrality. The framework of body neutrality encourages individuals to recognize that, yes, I have a body, and basically leave it at that. My body is not good or bad. Its purpose is not to appeal to the people who see it, whether in person or through a lens; it is to exist in unity with my soul, to enjoy this brief time on earth.

When I finally relented and bought some new jeans, I confronted the fact that I would have to size up. And then size up again. It wasn’t my favorite sartorial moment, but I felt proud of myself for being gentle with my body as it is now. To get back to my pre-pregnancy body I would have to spend every waking moment—not just the spare ones—trying to reverse time and gravity. For what? To wear a pair of pants that made me feel like my body conformed to an imaginary vision of beauty and thinness that I have chased since I was eight years old. But that time can actually be spent hanging out with my kid, who is exploding into personhood, with a sense of humor I legitimately find funny and a voice so sweet I want to embed it into every fiber of my being. Or rock climbing, which I love because of how it makes my mind and body feel, not just how it once made my body look. Or quilting or cooking or gardening. Basically anything that feeds my soul and not just my ego.

As Jessica DeFino put it, “I do think it’s important for us, individually and collectively, to shift the focus from looking fuckable to doing the actual fucking (if that’s what you want to do).”